If you’re a hiker or a backpacker, an altimeter can be a powerful navigation aid when used in conjunction with a map and compass.

Altimeters aren’t new, but they have fallen in price in recent years and are commonly included as a function in outdoor sports watches. For instance, I use a Casio Pathfinder Watch which has an altimeter (priced under $180) and is accurate to within 20 feet when calibrated. It’s completely transformed the way I navigate with a map and compass and has proven to be an indispensable navigation aid.

Here are a few examples of how an altimeter can help you pinpoint your location or guide you, both on-trail and off-trail.

Where are we along this trail?

Have you ever found yourself hiking up a trail covered by a forest canopy or lacking major landmarks and wondered how far you’ve hiked and how much farther you have to go? An altimeter can be used to pinpoint your location if you’re hiking in terrain with ups and downs and you have a topographic map handy.

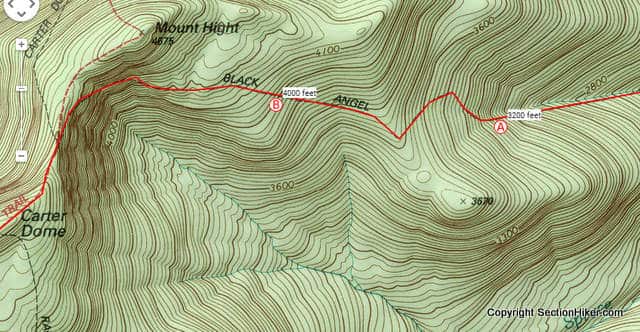

For example, let’s say you’re hiking up the Black Angel trail, in the map above, which climbs several miles to the summit of of a mountain called Carter Dome. If you had an altimeter watch, you could check your elevation anywhere along its length to pinpoint your location on the topographic map.

For instance, if you queried your altimeter watch at point A, you’d see that the elevation was 3200 feet. Knowing that, you can trace your finger along the Black Angel Trail to 3200 feet on the topographic map, and you’ll be located at exactly that point on the trail. The same holds for point B, at 4000 feet.

Have we lost more elevation than we want?

While an altimeter can be useful if you hike on trails, it really shines when you step off trail because you can use it to figure out if you’re where you want to be or whether you’ve strayed off course.

For example, let’s say you want to hike from Big Bickford Mountain to Scarface Mountain, passing through the saddle between the two peaks at 2680 feet of elevation and following a compass bearing along the RED route. If you had an altimeter, you could check your elevation as you descend Big Bickford to make sure you don’t drop below the elevation of the saddle and off course. For example, if you found yourself at 2550′ feet, you probably fell of the RED route and followed one closer to the BLUE route.

This is quite an easy mistake to make when coming down a mountain, even if you’re hiking along a compass bearing. If you have to hike around fallen trees or other unexpected landforms, it’s easy to lose more elevation than you want. But checking your route with an altimeter as you hike can help you discover that you’re off course sooner and help you course correct faster.

We want to follow a constant elevation or contour around an obstruction.

The tops of many mountains are often covered with blown down trees and can be very difficult to traverse. One option is to avoid the blow downs by walking below the summit plateau at a more open elevation. Called following a contour, this can be difficult to do without losing elevation and increasing your energy expenditure to get it back, or climbing too high and losing speed amidst the obstacles you are trying to avoid.

For example, if you approach Sable Mountain, pictured above, from the north, one strategy for avoiding summit blow downs would be to climb the north ridge to 3200′ and to hike along the west-facing 3200′ contour until you get close to the actual summit on the south end of the mountain. The slope gradient below 3200′ is much steeper on the west face, so you wouldn’t want to drop below that elevation. However, side-hilling at a constant elevation can be tricky to maintain for any distance, and being able to refer frequently to an altimeter can be a big help in contouring around such a large obstruction.

Altimeter Calibration

The previous examples help illustrate some of the ways that an altimeter can be used for on-trail and off-trail navigation when coupled with a map and compass.

Most altimeters base their elevation measurement on the change in barometric pressue that occurs when you climb to a higher elevation or descend from one. Barometric pressure is also affected by changes in the weather, which can throw off your elevation reading if you don’t recalibrate your altimeter at least once a day.

Calibrating a barometric altimeter is quite easy, but it depends on knowing your exact elevation when you calibrate it. The best way to find your current elevation is to look it up on a map (if you know where you are) and adjust your altimeter by adding or subtracting elevation (feet or meters) to its current reading so that it matches the elevation of your current location. If you don’t know your current elevation, it’s best to hike to a known location on your topographic map and recalibrate your altimeter there.

SectionHiker.com receives affiliate compensation from retailers that we link to if you make a purchase through them, at no additional cost to you. This helps to keep our content free and pays for our website hosting costs. Thank you for your support. |

SectionHiker.com Backpacking Gear Reviews and FAQs

SectionHiker.com Backpacking Gear Reviews and FAQs

I have used them for a couple years. The major problem compared with a good GPS signal is the way in which they read. Since the weather often is changing as you hike, it gets off pretty easily. I have calibrated mine in the morning, at a known location, and by 1000 they it was reading a 50′ difference compaed with my GPS. I pretty much gave up on the barametric devices. We often get at one sometimes two fronts through the ADK’s. While handy for rough guestimates, they are not real usefull for the navigation you describe except in a three day rainstorm or with two or three days of good weather. Often the pressure will not change much during these times. This was with an old Timex Expedition I wore for about 8 years.

I don’t usually carry either an altimiter or GPS, anymore. Even my compass can be effected by local iron deposits/rocks in an area. The ADK’s especially seems to have large deposits of pyrites or ore bearing rocks in some areas.

They are great for checking against your compass, though. Near some ocluded peaks, it is hard to know exactly where it is. It often registers a change in elevation, whether that change is increasing or decreasing, over short distances. Skip the numbers, since they are often 20-100′ off, though.

I rarely have to recalibrate my altimeter during the day in the whites, but I also check to make sure it’s continuously calibrated whenever I reach a known location like a trail junction, handrail, or summit. But like all navigation tools, you need to always make sure your other navigation information is in agreement when you take a reading such as your compass and what you think you should be seeing on a map.

If you are having problems with magnetic rocks, you should try bruntons new compasses which have a magnet inside them that keeps them from being affected by local magnetic forces. Clever idea really.

This seems like a very valuable tool. I’ve used the built in barometer in my phone for things like this. A lot of Android apps will take advantage of the extra sensor to calculate your altitude in addition to a GPS fix. I know there are a lot of factors that can throw off the reading by quite a bit, I find my phone isn’t always accurate right away with the barometer by itself.

My altimeter has completely transformed my hiking experience, as much as my first water filter did, if not more. My wife gave me an altimeter watch last December and ever since then, I now feel completely unconstrained by the presence or absence of trails. It complements a compass and map that much…and if you pay attention, you can know where you are pretty much all the time.

I purchased my first altimeter watch earlier this year. I was playing with it during a couple of overnight trips. In July, I took a 12 day backpacking trip with my son’s scout troop to Philmont. While it is nearly impossible to get lost I was able to hone my craft with the altimeter. We had some crazy weather blow in which showed some of the limitation but it also work amazingly well. Another dad had a gps unit and we were always within 20 feet of each other, of course that could mean we were both off.

An altimeter is now a must have in my book.

I’ve used an altimeter in similar fashions but did pick up some other useful scenarios from this discussion.

I had a LaCrosse Technologies altimeter watch until the battery died. Replacing the “non user serviceable” battery would have cost as much as a new watch, so I replaced the watch with an Axio Mini, which had easily replaceable batteries. The Mini didn’t have a thermometer, but I never found that useful on a watch anyway. The Mini got blasted off by the surf when I was boogie boarding in Mexico a few months ago and then I found out it is no longer made. I’m currently shopping for another altimeter watch and am using an app on my phone in the meantime.

I also use a free app on my phone called “High Altitude” which correlates the GPS location with the digital elevation module to give me local elevation, which I can use to calibrate my barometric altimeter. The DEM elevation is probably more accurate than the GPS altitude calculation. When I’m flying, I use High Altitude along with Backcountry Navigator in the “Record a Track” mode. BCN tells me how high and fast I’m going and High Altitude lets me know the elevation of the terrain I’m flying over. It’s a geek thing…

You probably know this, but if you turn take an altimeter reading on a commercial airplane flight, your elevation will be between 7500 and 8500 feet because that’s the barometric pressure that the cabin is pressurized too. Good way to get aclimated before you arrive in Denver…

Most jetliners have a cabin altitude of 7500 to 8000 feet. I’ll have the barometer going also so that I can see what pressurization they are running. Backcountry Navigator gives me GPS altitude, which is fairly close to cruising altitude, although there might be some difference between actual altitude and cruising altitude because above 18,000 feet all aircraft are using 29.92 inHg for the altimeter setting.

I usually have three apps going:

1. High Altitude: This gives me DEM elevation of the terrain directly below me.

2. Backcountry Navigator: This gives me GPS altitude, along with heading, ground track, and ground speed.

3. Altimeter: This gives me cabin altitude (usually 7500 to 8000 feet).

I’m never bored…

I’ve heard a lot of good things about BCN app, but haven’t used it yet. I’m always on the lookout for other Android apps. Do you have any other recommendations that you have tried or is BCN pretty much the “go-to”? Right now I have Locus maps, Maverick, and AlpineQuest installed on my phone. As you can see, I have a hard time finding an app that works best for me.

I’ve dabbled with Locus and a few others and have been VERY happy with BCN. It costs about ten bucks, but I drop that on a topo map in any National Park I visit. The developer is very responsive and quick to follow up on any bugs or suggestions. There is a wealth of free topographic and photographic imagery sources available through the app. There are even sources for other parts of the world.

My brother, who could make Jack Benny look like a spendthrift, tried many free sources of maps and ended up settling on BCN. He loves it.

When I’m hiking in a new area, I’ll download a gps track from somewhere to the app and then have a trail map.

It’s the best app I’ve purchased.

It’s nice to hear that BCN has additional maps that you can download for free, I looked at getting the full version of Trimble Outdoors for $4, but then they charge something like $60 for topo maps! At least BCN has a 14 day trial so I might do that for my next trip and try it out and see how I like it compared to the other ones. Thanks for the suggestion!

Gaia is also a useful App.

If you have an Android device get FDroid.

On the FDroid repository you can find open source apps and some I’ve found that I use back country are Open Street Maps and TrailSense. Electronics fail though. Batteries don’t like to get too hot or too cold. Batteries, chargers etc are heavy and bulky. GPS signals, cell phones signals and radio signals are limited or unavailable in the true back country. I use Sun Company Ascent Altimeter. It makes it fun and easy to track weather patterns, barometric pressure and altitude. An instrument as delicate as a barometer needs to be rugged and calibrated frequently. Knowing how to use it can make life easier and reassure the uninitiated with back country navigation.