GPS smartphone navigation apps are convenient to use and a real boon for making outdoor navigation more accessible, but they’re best used alongside other navigation tools such as waterproof maps and a magnetic compass. If you’re just experimenting with navigation apps for hiking, backpack, backcountry skiing, climbing, or hunting, it’s easy to overlook their deficiencies. But if like to explore areas farther afield or in great detail, you’ll quickly encounter issues with the accuracy of the information calculated or displayed by them.

That doesn’t mean that GPS navigation apps are any less valuable for backcountry navigation, but it’s important to understand the new issues that they introduce beyond those inherent with traditional paper maps and compass-based navigation, including:

- Imprecise distance calculations

- Outdated map layers

- Summarization issues associated with zooming

- Compass miscalibration

Imprecise Distance Calculations

If you’ve ever tracked yourself with a GPS navigation app, you’ve probably noticed that the mileage reported by the app differs from the mileage on a paper map or in a guidebook. This occurs because mapmakers use much more precise tools to measure distance and plot routes than recreational users. PMags has a good article (GPS Mileage Discrepancies) that dives into the nose-bleed details, which I’ll summarize here.

Recreational GPS receivers, like those built into smartphones or dedicated GPS units, are less accurate and far less expensive than the professional GPS receivers used by mapmakers. Professional units are more sensitive and can connect to more GPS satellites providing a more accurate triangulation “fix”. Recreational GPS units can only provide an accurate position fix 95% of the time but can be off as much as 7.8 meters (25.6 ft) the other 5%. These errors add up over time, especially in areas with poor satellite coverage (where the error rate is higher), resulting in distance differences that usually vary by about 10%. That might not sound like much but it adds up over long routes or when you’re hiking over challenging terrain.

Some mapmakers also use a measuring wheel or 100-foot long tape measures and clinometers to measure trail distance and elevation gain. These non-digital measurement techniques are considered more accurate than professional GPS receivers because they measure all the little ups, downs, and turns that hikers make when following a trail and not just a sampling of them. Regardless, all three of these mapmaking techniques explain why recreational GPS navigation app records different mileage than those shown on trail signs, in guidebooks, and on paper maps.

Outdated Map Layers

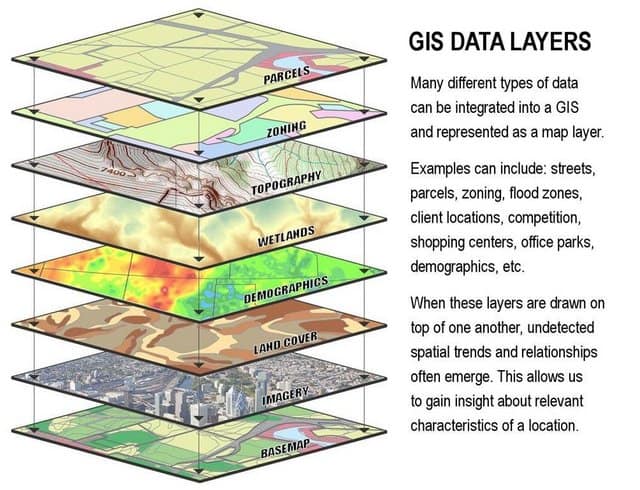

Most of the maps that are displayed in smartPhone GPS navigation apps are stored in geographic information systems (GIS) in what are called layers. Each layer represents a different group of geo-referenced data points that are superimposed, one on top of the another, to create a composite map image. For example, you might have a base topographic map and several separate layers that depict:

- Trails and trail names

- Mountain summits and their elevations

- Ground cover including areas with and without vegetation

- Streams, rivers, and wetlands

- Contour lines

- Slope shading

These data layers come from government agencies, open-source or crowdsourced data collection projects, and private companies. Problems can arise however when data in these layers is out of date. For example, the route that trails, streams, and rivers take across the landscape can be quite dynamic and change frequently. Trails are closed, abandoned, or rerouted far more frequently than you might imagine. The same is true of streams and rivers as the result of floods.

Here’s an example of a trail (The Black Brook Trail) in my neck of the woods that was closed and abandoned by the Forest Service over 10 years ago but is still displayed on the Gaia Topo base map in GaiaGPS. It’s notable because I think there’s an expectation that trails displayed on maps are current and up to date. However, I can show you additional examples in New Hampshire’s White Mountain National Forest where abandoned and closed trails are still displayed in GaiaGPS, in addition to misplaced mountain summits and incorrectly located trailheads.

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to data currency and quality control in smartphone GPS navigation app maps. The problem is that no one is actually checking to see whether the map data included in most GPS navigation apps is accurate and up to date. I don’t know where GaiaGPS got its trail data for this map, but the problem of data currency and accuracy is even more of an issue when trail data is open-sourced and/or crowdsourced and not licensed by a land manager or publisher invested in keeping it accurate and up to date.

If you take a look at Guthook’s Guides, which I also use, they’ve solved the data currency issue by severely limiting the amount of map data they display in their apps and by hiring people to hike the trails to keep their GPS data current and accurate. There’s something to be said for a curated approach like that since Guthook’s Guide for the White Mountains, which doesn’t display the abandoned Black Brook Trail shown above (For more on this issue, see: GPS Enabled Trail Guides vs General-Purpose Navigation Apps).

Summarization issues associated with zooming

Most GPS navigation apps let you zoom into a map giving you more information about an area, or zoom out to hide details when you want a less detailed overview. This is one of their great strengths, the ability to store and explore a huge amount of mapping data. But the zoom function also hides a lot of detail that can be important in planning and navigating routes. In most GPS navigation apps, you need to remember to zoom down to the highest level of detail to see all of the trails, land features, water features, property boundaries, mountain summits, item labels and such, because a quick glance at the map displayed on your phone can hide them.

In contrast, paper maps always depict all of their details at once (the equivalent of maximum zoom) because they only capture a small area compared to that depicted by a GPS navigation app. This is why it can be handy to carry a local map with you in addition to a GPS navigation app, particularly since they are generally checked, updated, and republished more frequently than online data layers.

GaiaGPS does a pretty good job with zooming and summarizing user data. For example, I have waypoints in GaiaGPS for the 500 highest mountains in New Hampshire and they can really clutter up a smartphone map. When I zoom out and want less detail, GaiaGPS collapses multiple waypoints into a single icon and puts the number inside it, so I know that more detail is available if I zoom back down. That’s very handy.

But the same zoom capability can also introduce map artifacts that don’t exist in the real world and never have. In this example, the Hubbard Brook Trailhead (left) is correctly located. But if we zoom in a bit, it is renamed the Cushman Trailhead, which has never existed. I have no idea why this occurs, but it’s clearly related to the app’s zoom function. Note: This error only occurs in the GaiaTopo basemap as far as I can see and not other basemaps.

Compass Miscalibration

Have you ever noticed how the direction of travel icon on your GPS navigation app is not pointed in the direction you are traveling? Or how Google Maps, says “turn north in 200 feet” instead of “turn left in 200 feet.” This is because your smartphone’s compass doesn’t know which direction you’re headed.

There are a couple of potential reasons for this which are usually described as a miscalibrated smartphone compass. This occurs because your smartphone’s GPS receiver can’t connect to enough GPS satellites to get a position fix, especially if you haven’t changed position for a while, which is used by a GPS navigation app to figure out which direction you’re headed.

You can often reset a miscalibrated compass by waving your smartphone in a figure 8 motion above your head, turning location services off and back on, or restarting your phone.

The trick is realizing that your GPS navigation app’s direction of travel arrow is not pointing in the correct direction before you start walking the wrong way. This is where consulting a map, paper or electronic, or a simple magnetic compass comes into play. You can check that your navigation app is pointed in the right cardinal direction with a simple magnetic compass like the Suunto Clipper or by identifying map features that correspond to what you’d expect to see if you’re headed in the correct direction.

Wrap Up

I’ve detailed several ways in which GPS navigation apps can lead you astray. While knowing about them is important, how can you avoid a nasty surprise? The answer is pretty simple. You’re going to want to use all of the navigation tools available to you – apps, multiple maps, and a magnetic compass to make sure that you have the correct information for planning and following a route. Redundancy increases certainty in the inherently uncertain pastime of outdoor navigation.

While the extra maps, map layers, and position fixes afforded by GPS navigation apps are incredibly powerful tools for planning and following routes, it pays to check them using multiple sources and tools when planning or navigating in the field.

SectionHiker is reader-supported. We only make money if you purchase a product through our affiliate links. Help us continue to test and write unsponsored and independent gear reviews, beginner FAQs, and free hiking guides. SectionHiker.com Backpacking Gear Reviews and FAQs

SectionHiker.com Backpacking Gear Reviews and FAQs

“Importance of Data Quality and Technological Limitations in Mapping Apps”

There, fixed the click bait histrionics for you.

I think it’s important that people understand the limitations of existing GPS apps and applaud Philip’s efforts to get the word out. You may think you’re witty and smart but I think the guy deserves a pat on the back for posting quality content even if his title is an attention getter. I can’t see Backpacker or Outdoor Magazine ever running a story like this because they have their fingers in the same til as the app companies.

John – I think you missed the point of this article, which is that one should use all of the tools at one’s disposal: app, maps, and compass for navigation and not just count on apps. Yes, they have issues including data quality issues, as well as the other technical deficits I describe below, but you can often figure things out if you use multiple tools to crosscheck their output.

I once had a navigation instructor who encouraged me to always validate my navigation decisions using 3 different methods, including terrain association, compass bearing, trail signage, elevation, etc. and it really does help you catch errors. That might be overkill for most people, but I use it to illustrate the point.

I got the point, see my response to Cathy’s comment below. The post has a lot of good information but the article title was a poor choice that set a tone that continued throughout the post. You can debate it’s snark or clickbait nature, but use of the word “lie” is incorrect. A lie is an intent to mislead. What you describe are not lies but are the natural lifecycles of cartography and limitations of technologies – not any nefarious intent by a map publisher, software engineer, or hardware manufacturer. The important point on any navigation tool whether it be a paper map, app, GPS or compass is that it’s no different than any other item of gear. You need to know it’s limitations, potential failure points, and proper usage. This is especially true with apps and GPS units. I’m a professional geologist with decades of mapping and navigation experience who concurs with your navigation instructor. Don’t be that hiker that walks off the cliff because your app or GPS tells you to – and if you do, it’s probably user error rather than an conspiracy at Garmin, Gaia, and USGS.

John. It’s the Internet. You have to use outrageous post titles to get people to read serious stuff. Get over it.

When you spent all day spot and stalking that buck and finally put an arrow thru it at 10 minutes before legal shooting time is over then quarter it and put all 100+ pounds of said deer on your back and start your hump out to the truck a few miles away only to find the trail on your app is not there that absolutey qualifies as a lie. Webster is not always right in definitions and dont bash Philip for callling it like it is. Just because the truth hurts…Keep up the good work Phillip. Those trolls will always be part of the internet too….

Another good example is a missing bridge across a big river that you can’t ford because it was removed 20 years ago. That kind of crap just ruins your day.

You make a good point about the layers being out of date, especially for trails. That doesn’t have much to do with the app or with GPS, though. Unfortunately I don’t think there is *any* source showing trails that is kept up to date.

The problem is especially difficult when you are not on National Park or US Forest Service land. State parks and forest agencies don’t usually generate good maps.

Many of the best maps for use outside National Forests and Parks are still the old USGS topos, which may be 50 years old. Fortunately terrain features don’t change quickly in most cases, and even structures and roads are relatively stable, especially outside developed areas. For example, in the Adirondack State Park, I have not found any better maps than the old USGS top layers.

The newer USGS topos have more accurate landforms from remote sensing, but are missing all the detailed structures from the earlier version. The nice thing about the apps is that you can have both available.

For trails, looking at online trip reports and crude official maps from state or federal agencies is about the only way I’ve found to get more current data.

For example, the DEC site for NY has very crude maps with no topo lines and few details that nevertheless show where the trails are that they consider active and many designated campsites. These maps are not adequate on their own for serious use, but are good as a cross-reference.

The Forest Service has a series of GEOPDF and GEOTIFF maps using the map data also used for the newer USGS maps, but with FS assets added on top. The quality of the asset information varies by forest, but the quality of the topographic data is questionable in certain instances. It seems to have been smoothed out so mountains are missing their tops and cliffs become apparently walkable slopes. I’ll use these new maps to follow trails, but revert to older USGS for peak bagging.

I have been finding Open Street Map to be a really good resource for trails, depending of where you are. I use it offline with topo lines with files from Open Andro Map in an appropriate app. (These are Oruxmaps and c:geo on my phone. Yes, I geocache sometimes. Many others are available.) When I get back from hiking a place with no trails at all on OSM, I settle in and make sure to add those, including such attributes as “trail visibility”. (An abandoned and unmaintained trail may still be hikeable, but there should be some indication that it might be hard.) This doesn’t just help other OSM users. A lot of other maps pull from OSM. In fact, that may be where the example odd trailhead label is coming from in the example. That is a problem with user generated data. I try my best, but I make errors. The more people who go ahead and edit it, the more likely it is to be correct.

One issue I’ve heard about recently is people documenting trails across private property which are actually not open to the public. Apparently, it’s very hard to get the removed from the OSM and apps that pull data from it, because they do so infrequently and don’t receive the updates.

A good source for trail maps in the NY and NJ area are the ones available from the NYNJ Trail Conference. They are excellent maps that are updated regularly and are available as print maps on Tyvek or through the Avenza Maps store in the Avenza app.

You raise a good point regarding maps becoming outdated. The unfortunate reality is that cartography is expensive to produce and maintain. Outdated maps are not telling a lie (as there is no intent to deceive), but things do change. A map must be considered nothing more than a snapshot in time. Likewise, GPS technologies do not lie, but have many factors that affect their accuracy and precision – from design to satellite position, to topography. Maps and navigation aids are like any other piece of potentially lifesaving gear. Users need to know not only how to use them, but also their limitations.

I think the difference in this case is that the NYNJ maps are regularly updated (and excellent) and that Avenza loads the equivalent of monolithic georeferenced paper map images not map layers. It’s very different technology than that used by Gaia or On X.

Well the app is charging you money for access to the maps and they in turn pay license fees to people who sell them data layers. Don’t you think there should be some commercial accountability for map accuracy. The least they could do is tell you when the data layer was last published.

A few issues I’ve found with GPS apps and maps are:

If you’re using a battery saver mode, some apps don’t accurately show your track, truncating your route, cutting off switchbacks, etc. This can make your traveled distance show less on the GPS than the measured trail mileage. This was worse on earlier GPS units that also had trouble with tree cover.

Some units that have trouble keeping a position fix will show you traveling all around an area you may be resting at. I’ve had that happen–my track looked like that of a scatterbrained squirrel when I left the GPS tracking on overnight. I didn’t know I’d hiked that far while sleeping. I must have an unknown sleepwalking problem!

On the newer series of maps, contour lines are computer generated by averaging between elevations in a point cloud generated by satellite. This smooths out the contours and makes cliffs just look like steeper slopes. For the topography, I prefer the old USGS topo quads that will show contour lines stacked on top of each other. Those maps are much more accurate on a local level. Of course, the trail data may be out of date. I’ve also found established trails on some of the older maps to be marked a bit out of position compared to GPS tracks.

It’s good to use all the tools available. A compass weighs less than the battery in your phone and doesn’t quit working unless you step on it.

Your phone compass may have drifted as well and sometimes it can be confusing about which way to hold your phone so that the arrow on your display is pointing the direction you’re looking. I’ve had the arrow pointing off to the side and a few times while hiking off trail, I had to get quite creative to figure out which way it was telling me I really needed to go.

I have little confidence in the compass of my phone or ABC watch. If I need anything beyond a very rough check, I’m going to pull out my “real” Suunto compass.

The compass feature in the watch and phone does work if properly calibrated, but its not going to be very precise.

On a trip a couple of days ago, I missed a turn in the trail right after a stream crossing, and climbed several hundred feet up a hill before realizing I was off the trail. My phone GPS with Gaia calculated the correct bearing to my destination, and my compass showed me where that actually was. Returning to streamside showed the continuation of the trail on the expected bearing.

Use each tool for its intended purpose, and they can be a big help.

The compass on an ABC watch is generally useless for the simple reason that it’s hard to hold flat. I also have little faith in GPS compasses. Hard to explain why – I just find them very susceptible to local topology – since they are not based on magnetism. I only use a baseplate compass. And I carry two!

@Granpa. Hmmm. I just returned yesterday from two weeks at Philmont Scout Ranch and let me tell you I was cussin’ CalTopo and Gaia. Maps I created (at home prior) in CalTopo and imported (at home prior) into Gaia did NOT work well at all in either app. It never occurred to me that using power saver mode on my phone might affect the two apps. Maybe that’s what it was, but I still have to try to recreate the problem at home to learn how to avoid it in the future. We found the PSR maps to be a bit on the small scale side in many circumstances. I’d advise future crews to print larger scale maps of their trek area as another resource.

Some apps like CalTopo(SARTopo) will let you stack layers and alter the transparency. For large parks or state/national forests, I’ll use the USGS topos as the base layer and then add the OSM at 50% transparency. That lets me see the contour lines but adds the updated trails. Another good combination is the USGS topos and satellite imagery, so you can see fields or new structures.

I actually think Philip is justified in using the word “lies”, even though he used it as an attention getter. Although, maybe con-job will be better. Guthook publishes accurate trail information and has people verify it, , but Gaia is deliberately and knowingly publishing out of date and incorrect information. They have the means to check it but don’t. WTF?

I use Guthook a lot. I love it. But using it on some place of the PNT it’s a rough guideline at best. I know the PNT is a work in progress, but there are places where there should be some discernable track according to the map and there’s nothing there. I use Guthook in conjunction with older USGS 7.5 maps — the Avenza app lets you download the older versions for free — and I find the older maps more accurate even when a trail has been decommissioned. (In the drier areas of Eastern Washington, nature doesn’t reclaim trails as quickly as it does in the Cascades & the Olympics.)

Sometimes I just chalk up the wildly incorrect information as the app’s version of a ‘trap’ street. Although the time I came to a 45° slope where the 7.5 map said an decommissioned trail was supposed to be I realized that tromping in less-traveled areas requires a great deal of flexibility. (No evidence of a slide. Just a sheer drop-off even a miner wouldn’t climb. I can’t imagine there was ever a trail there.)

I agree that dates on the map layers in the app would be a good thing.

It’s unlikely that a small company selling data access through an app has the resource to check and update the data layers. They are not the source of the data. They pay the provider for its data and it is the provider’s responsibility to maintain it.

The real problem was pointed out by John. It’s very expensive to create and maintain maps, especially when you need check ground truth with humans at the site. Because of that, we’ll rarely ever have completely up to date trail maps.

Web sites like this one add great value with recent trip reports that show actual ground truth at the trails Philip visits.

But GaiaGPS is not a small company anymore. It was acquired by a company that purchased Outside Magazine, Outside TV, Backpacker Magazine, Peloton, SKI, Climbing, Yoga Journal, Rock and Ice, Gym Climber, Trail Running, VeloNews, VeloPress, BRAIN, Triathlete, Beta, AtheleReg, and SNEWS among others. It is completely in their capacity to increase the accuracy of the maps they provide consumers. If Guthook can do it with a handful of employees…

Interesting and thought provoking discussion. In my line of work, shipping an app that has bad data would be considered a software bug, one that customers would demand be fixed.

What I wonder is why the word ‘lies’ generates such a strong reaction here, when Philip used it previously in this https://sectionhiker.com/why-do-hiking-maps-lie/

There the omission of trail information is deemed intentional. So why would you deem it unintentional in a GPS app. The app maker is actively choosing which data layers to bundle and publish in the form of a new ‘work.’

I think a better article might be one that details the errors inherent in all sources. On more than one occasion having a GPS with an absolute location saved me because my paper map was not current despite being only a couple years old and purchased immediately before the trip.

Good article Philip. I use the GAIA app and carry a map but I think we rely too much on apps and maps. We need to use our internal compass more.

Why the emphasis on smartphone gps? by far the best solution to this problem is a Garmon GPS. They have excellent but-in maps, don’t suffer from the phone map problems you’ve mentioned, and are relatively cheap. and the batteries last far longer.

I have some bad news for you. The 100k topo maps that Garmin ships were last updated in 1990 and are very low resolution. While they do sell 24k maps for an add-on fee, they pay nothing for them because they’re freely distributed by the USGS and were also last updated in 1990, when the USGS stopped checking field data for budget reasons. It’s a scam.

If you want better maps for your Garmin for free, I suggest you check out this article, although you’ll still experience many of the same reliability issues as the maps bundled with smartphone apps. Garmin inReach maps (based on delorme’s maps) are even worse and can’t be updated at all.

https://sectionhiker.com/free-garmin-gps-maps/

While some of Garmin’s receivers are more sensitive than the GPS receivers built into smartphones, they still suffer from the distance errors that smartphone apps suffer from.

The reason I focus on apps in this article is because that’s what the vast majority of hikers use. Why pay $500+, plus the added fee for 24k maps when you can get all that for $30/year and get a much much wider selection of maps? Battery use is also less of an issue on Smartphones than you probably realize. I get several days of use out of mine with just a few simple energy-saving techniques.

The only advantage to using a Garmin GPS in my mind is the ruggedness of the device, which is seldom an issue unless you hike off-trail. Long answer.

I second that Garmin 24k trail data is garbage. 1990 is being charitable. Try building a route on the AT in MA. The bigger problem is that trail segments aren’t connected- leading to strange behaviors when crossing roads.

Ill 3rd that Garmin 24K garbage. It punched me hard on a wildfire in AK. Roads and trails and traplines where there were none shown and vice versa. Even the local airstrip has been moved but not shown on the GPs correctly. Yukon River had done its thing a few times as well and moved some of the bordering swales and islands. Thankfully the native population there could set us straight and drew us a map with a sharpie and 6 MRE boxes fiber taped together. Phone service there just plain did not exist so apps were useless as well. Wish I had done some GPS homework BEFORE I went. Pretty sad when recycled boxes and a .50 marker do a better job then several hundred dollars of electronics

GPS uses trilateration, not triangulation.

I did not know that. Thank you.

Trilateration works by finding your position on Earth once the location of GPS satellites orbiting the Earth and their distance from your location are known. … But with a third satellite signal we can tell the exact location of our device, because the three spheres will intersect in one point only.

Do the altimeter readings on my smartphone and ABC watch suffer from the same accuracy issues?

Also, my watch often records mileage readings greater than Gaia. Is there a reason to believe one is more accurate than the other.

Altimeter readings on a smartphone are based on GPS signals which are very different than altimeter readings on an ABC watch which is based on barometric pressure and much be checked and reset them periodically at known elevations. I generally find GPS elevations accurate and set my ABC watch to use them. An ABC (altimeter, barometer, compass) watch is different than a GPS-enabled watch though.

Your watch uses different software than Gaia, which probably accounts for any mileage differences.

Good article. I had a career as a map maker, mostly for government contracts and concur with your assessment. I have learnt the hard way to also carry a copy of hardcopy paper map with me in a zip lock bag. I seldom use it, but occasionally my phone runs out of power or locks up. Then you really realize the importance of redundancy. In addition to a small compass, I also carry a small altimeter/barometer. This I find very useful in our mountainous coast – elevation is the most useful indicator of position and progress when you have paper or electronic contours. Also, I can glance at the altimeter in a second, instead of unzipping my phone – very convenient. AllTrails is my favorite navigation ap – just started using their edit functions; where at the end of a hike I can updated the trail assessment and suggest corrections to the curator(s) – this is probably the only way to keep trail maps up-to-date, by user updates – not dissimilar than posting the latest trail conditions/issues for the next group of hikers.

I like the fact that I can keep track of my elevation on my ABC watch. It is faster to check as you note, saves the phone battery, and means I can ignore my phone and keep it packed away on long ascents.

I’m just not convinced that the current methods of public data collection are structured to collect accurate information.

Just to add some data info via my career in map making:

Digital USGS topo maps do not show detailed contour lines like the old analog printed versions. Maps started being scanned and digitized in mass in the 1990s. Computers and especially memory were no where near as powerful as your typical modern cell phone is today. So the amount of data had to be dumbed down to fit the hardware. Data points were spread out, for instance 100 feet apart. Much detail was lost in the fine contouring. Ragged moutain top appear as smooth. Cliffs on a 10 or 20 foot contour increment disappear on 40 foot contours. And so it goes. The one tool that could really help in field verfication, at least with structures, are drones. But it takes an organization dedicated to accurate maps more than the tools used. The USGS has been hacked for decades by the politicians and thus little funding for maps exist.

One thing I really like about Cal Topo is the layer control. The ability to have an old USGS scanned topo layer in 50% transparency over the modern digital version is invaluable. You get modern features, but reference to more accurate contours. The real problem is that most of the public has not a clue and takes whats given them as the de facto – the bridge not there, the trail washed away in a slide, the river that changed course in flood. Not to mention thousands of acres of wildfire altering nature. National mapping should be its own department, a separate entiry, not part of NFS, NPS, USGS, Dept of Commerce, etc. One would think that in the era of GPS which is a huge factor in daily lives via rhe shipping/delivery industry, that constantly updating maps would be a priority. But that is my biased opinion as a map fanatic.

If your compass’ azimuth is in error, determine if the error is repeatable.

If the error is repeatable, then the error is predictable.

If the error is predictable, then the error is correctable.

Smartphone electronic compass residual (after calibration) azimuth deviation errors are correctable!

I am not sure I understand why the crowd sourced trail locations are not the way to go. I understand that there needs to be an appropriate algorithm to weight the different routes people take. It also would be nice if there was a way that apps identified how old the data was on different routes. I understand the parks may not like them if they are trying to close a trail. The Mount Isolation winter bushwhack track is on my phone app I assume because it was crowd sourced I don’t find that on any paper map I have. I am sure I am missing something but I assume that is how you get up to date trail location. Not guaranteed to be accurate but it seems to be pretty good. I am sure I am missing something though

Because they don’t take into consideration private property amongst other factors and once published they’re impossible to remove.

With respect to the rocky branch and iso express bushwhacks out to Isolation, you need to realize that those are not maintained trails and that the route changes everytime there’s any snow. There’s been at least one rescue this winter when someone tried to follow their GPS track out to isolation only to find themselves in deep snow because the actual route had changed. GaiaGPS does not distinguish between maintained trails, herd paths, or bushwhacks which is a big problem if you don’t now how to navigate across open country.

Thank you for clarifying. I have not used GaiaGPS yet. I have an old app that shows named maintained trails and then “tracks” from other people as different colors(I can’t update it though since they removed that feature haha). They need to have a finite persistence though and give dates for other “tracks”. I do see the issue though. It doesn’t seem like a great idea to blindly follow any one map and unfortunately probably best to just leave them off since some people do. I had a car GPS years ago that tried to direct me in to a lake. Luckily at the last second I was able to look up and look out the windshield. It was a tough choice whether to trust the GPS map and drive in to the water or trust my own experience and not drive a car into a lake. I was lucky that day and made the right choice but it could have gone either way.